One of the main drivers of the 2008 financial crisis was lending to borrowers with inadequate ability to repay their mortgage loans. In response, Congress enacted the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, which created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) and established an ability-to-repay/qualified mortgage (ATR/QM) standard. Dodd-Frank went beyond previous federal regulations and consumer protections, including the Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act (HOEPA) that had previously defined a class of higher priced mortgage loans (HPMLs).

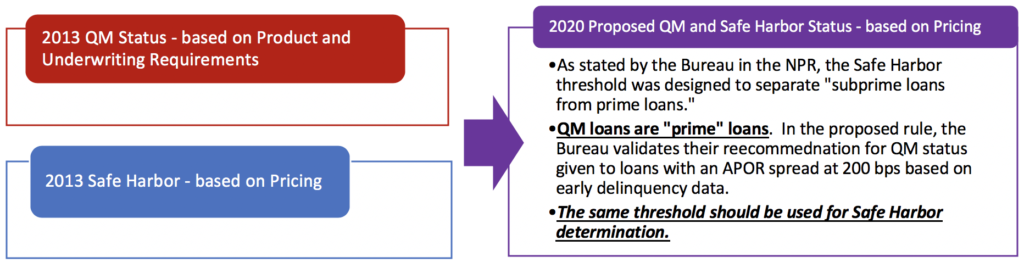

Going beyond HPML to address some of the underwriting concerns in the marketplace, Dodd-Frank created specific mortgage product restrictions and required the CFPB to promulgate a rule defining Qualified Mortgage based on specific underwriting criteria. As promulgated in the 2013 final rule, QM and safe harbor were measuring two separate things so different standards made a certain amount of sense. The QM standard was based on product and underwriting requirements, while safe harbor was based on loan pricing specifically assessing whether the loan was a HPML.

The CFPB is now seeking to update the regulation. In late June, the Bureau issued Notices of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) on the general QM definition under the Truth in Lending Act (Regulation Z) and the GSE Patch. The CFPB proposes to change the current QM standard in favor of a pricing threshold based on the difference between the loan’s annual percentage rate (APR) and the average prime offer rate (APOR) for a comparable transaction. The proposed rule would define a QM as a mortgage loan which is priced not more than 200 basis points (bps) above the APOR.

Unlike the 2013 final rule, the QM standard and safe harbor are measured using the same price metric under the new proposed rule. Having two different pricing thresholds to determine QM and safe harbor loan status creates an unlevel playing field that will arbitrarily shift borrowers to mortgages backed by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and leave consumers with less access to mortgage finance credit—all based on an arbitrary line.[1]

While USMI will comment on other aspects of the proposed rule, we think that one of the most significant issues within the proposal is the safe harbor pricing threshold. Based on our analysis of mortgage originations, loan performance, market dynamics, and the need to ensure consumer access to affordable mortgage finance, we recommend that this threshold should be pegged to the same threshold as the QM status, which the NPR suggests should be 200 bps. USMI made this recommendation to the CFPB in a September 2019 comment letter in response the CFPB’s Advance NPRM.

In the 2020 proposed rule, the Bureau justifies recommending QM status be based on a pricing threshold to 200 bps using early delinquency data as an indicator of determining a borrower’s ATR, stating in the NPRM:

“…the Bureau tentatively concludes that this threshold would strike an appropriate balance between ensuring that loans receiving QM status may be presumed to comply with the ATR provisions and ensuring that access to responsible, affordable mortgage credit remains available to consumers.”[2]

Should the CFPB move forward to replace the current QM definition with one based on a pricing threshold, then the Bureau can and should increase the spread that is used to delineate safe harbor loans from 150 to 200 bps over APOR to be consistent with the threshold that the Bureau recommends for QM status in its NPRM.

Why moving the safe harbor threshold to 200 bps matters:

- Lenders don’t lend above the safe harbor line in the conventional market.The distinction between safe harbor and rebuttable presumption matters. Market data makes it clear that many lenders avoid making rebuttable presumption QM loans to avoid any risk of legal liability. This is evidenced by the fact that less than five percent of all the conventional market financing in 2019 was done above the safe harbor line. For all intents and purposes, the safe harbor line effectively defines the conventional market and changes to how the Bureau defines QM safe harbor will impact who the conventional market will serve going forward.

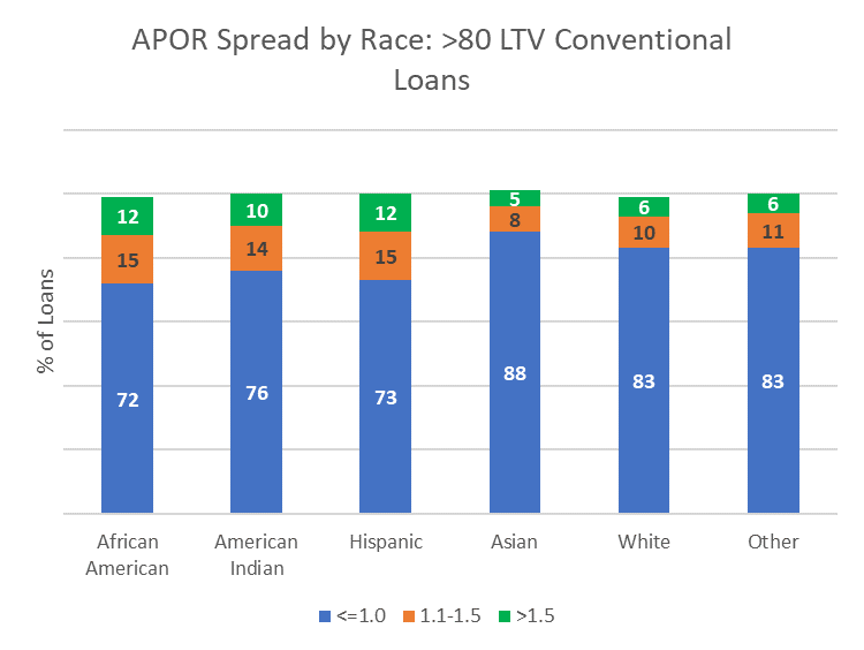

- Current recommended threshold disproportionately impacts Black and Latinx borrowers who are twice as likely as White borrowers to have conventional low down payment purchase loans outside a safe harbor of 150 bps. Under the proposed rule, many of the borrowers who are above the 150 bps threshold will be left only with the option of a FHA loan, which means they have vastly different competitive choices in terms of product offerings and loan terms—as demonstrated by the fact that there were approximately 3,200 HMDA reporting lenders for conventional purchase loans versus only about 1,200 for FHA purchase loans. This arbitrary line affects these borrowers’ credit options and leaves them with significantly fewer competitive options in the marketplace.[3]

- Creates an unlevel playing field. While the percentage of the conventional market above 150 bps is small on a percentage basis, this is not to suggest that there are not good quality loans above this threshold being done. FHA is five times more likely to have loans above the 150 bps simply because FHA calculates the APOR cap and APR calculation differently. HUD defines safe harbor as 115 bps plus the mortgage insurance premium, which is closer to FHA having a safe harbor threshold of approximately 200 bps, or even higher. Due to the discrepancies for how this threshold is calculated between the conventional and FHA markets, leaving the safe harbor threshold for conventional loans at 150 bps will arbitrarily distort the market and shift borrowers to FHA. This will give these borrowers fewer choices and shift borrowers from a market backed by private capital to the 100 percent taxpayer-backed market.

The Solution:

The solution is to increase the safe harbor pricing threshold to 200 bps to be consistent with the proposed QM pricing threshold. This will result not only in a more level playing field, but most importantly, by changing the threshold, the impact to borrowers can be mitigated. The volume of loans that would otherwise be left out of the conventional safe harbor market is reduced by almost 60 percent for the high-LTV market and reduced by over 50 percent for the entire conventional market.[4]

Increasing the safe harbor threshold to 200 bps above APOR will best ensure that we strike an appropriate balance between prudent underwriting, credit risk management, and consumers’ access to sustainable and affordable mortgage credit.

[1] 85 Fed. Reg. 41716 (July 10, 2020).

[2] 85 Fed. Reg. 41735 (July 10, 2020). Underlying and emphasis added.

[3] 2019 HMDA Data.

[4] 2019 HMDA Data.